.jpg)

Bum-badabum-badadadadabum-dead GIRLFRIENDS!

May 29, 2020

Imagine, for a moment, that you are an NBC executive in 1969.

Your network is airing such classics as Star Trek, I Dream of Jeannie, and Dragnet. A time-traveler asks you, "which of your prime-time shows do you think will be the most popular in future airings?"

You presumably take a puff of your cigarette before confidently replying, "Bonanza."

The time-traveler laughs and says, "Why not Star Trek?"

Now you laugh. "That childish stuff? No way. Bonanza's got 3 Emmys. Its endorsement deals sell all the color televisions and Chevrolet cars in this country. It's really popular in the European market. Plus it's even been in the Nielsen top 5 for 9 seasons straight. No other show has done that! Bonanza is definitely our best long-term investment."

And scene.

As I mentioned in our pandemic miniseries, it's difficult for most people born after 1970 to understand just how popular and influential the Bonanza TV show was. Among Gens. X, Y, and Z it is remembered, when it's remembered at all, as the namesake of the Cartwright Curse trope. Most Boomers reading this, on the other hand, already have the theme song stuck in their heads.

This is not to say that Bonanza's influence has completely disappeared. Reruns do still air on TVLand and other nostalgia channels. Its namesake steakhouse chain still has a few dozen locations. A few high-profile fans have worked references to Bonanza into 21st-century films: Quentin Tarantino dressed Django in Joe Cartwright's costume, while Guillermo del Toro's 1960s-set film The Shape of Water had the villain's wife insist "Bonanza is far too violent" for her children. Finally, the basic format of Bonanza called for a core group of moral characters to confront and solve ethical dilemmas every week - a pattern which one can still see repeated on modern shows like Grey's Anatomy and all incarnations of Law & Order.

Still, in the year 2020, Bonanza is not widely available on either DVD or streaming. Consequently, it has the least-active fanbase out of all our contestants. So before I tell you how women fared in the Bonanza world, let me establish a bit of context.

The Times

1959 was an interesting year. Fidel Castro took over Cuba. Music died in February. Richard Nixon & Nikita Khrushchev debated in a kitchen. Alaska became the 49th state and Hawaii became the 50th. Roughly 9 out of 10 American households owned a television. On the small screen, Rod Serling's Twilight Zone premiered, while on the big screen, the third adaptation of Ben-Hur came out. (Coincidentally, both of those have had two remakes since.)

The Babies were still Booming, and so was the glorification of traditional gender roles. If you were to judge by pop culture alone, you'd be forgiven for thinking that every American woman was busy with unpaid work, keeping house and raising kids. To be fair, that was a reality for many families. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics offers a more nuanced picture, though: about 1 in every 3 American women over the age of 16 was working outside the home.

Unfortunately for all the hardworking women in America, second-wave feminism was at least 4 years away. Employment ads were gender-segregated; unequal pay was a fact of life; employers could fire a woman for getting married or starting a family; and women's Social Security payments provided no death benefits for their children. On the East Coast, Ruth Bader Ginsburg had only just graduated from Columbia Law School.

On the West Coast, meanwhile, NBC's vice-president of programming, Alan W. Livingston, had just hired a writer/producer named David Dortort to write a pilot for a new Western show, Bonanza.

The Series

Bonanza centers on a family in which the women are all dead. I'm not joking: the premise of this series is that Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene) has been married 3 times (to Elizabeth, Inger, and Marie), and each of his wives has died, leaving him with 1 son apiece (Adam, Hoss, and Little Joe, respectively). With all 3 tragic backstories behind him, Ben proceeds to have weekly adventures with his three grown-up sons.

Yes, this does mean that the entire main cast was named Mr. Cartwright, a fact that was jokingly acknowledged more than once.

Messrs. Cartwright, Cartwright, Cartwright, and Cartwright live on a ranch called the Ponderosa, located just outside Virginia City, Nevada, in the 1860s. On various escapades they are joined by their Chinese cook, Hop Sing; Joe's half-brother from Marie's first marriage, Clay; Ben's nephew, Will; their ranch foreman/close friend, Candy; their other ranch foreman, Dusty Rhodes; Ben's [adopted] fourth son, Jamie; and someone named "Griff." This motley crew encounters all the usual Western stock characters: cowboys, Indians, miners, prostitutes, and various historical figures (including Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Emperor Norton), only some of whom were ever really in Virginia City.

When it debuted on Saturday, September 12, 1959, it was one of an incredible 30 separate Western shows on network television. But Bonanza stood out from all of its competitors in two ways:

- It was filmed in Technicolor, and

- It talked about Real Issues, frequently and verbosely.

As Brandon Nowalk of AV Club puts it, "There was never an issue that the Cartwrights couldn’t talk to death." Topics tackled by Bonanza's Very Special Episodes include interracial marriage, civil rights for the disabled, compassion for traumatized veterans, sensible gun control, and other hip 1960s issues.

Now, Bonanza was a product of its time, so it did champion certain views that are painfully dated. For example, the happy ending to "The Sound of Drums" (aired November 17, 1968) comes when Ben Cartwright convinces a group of Native Americans to relocate to a reservation with a minimum of fuss. I'm sure it was a blind coincidence that this aired 4 months after the founding of the American Indian Movement, which started its occupation of Alcatraz Island one year and three days later.

Other episodes delivered more successful morals, though, with the Cartwrights espousing radical positions such as "let's offer homeless veterans a safe place to live," "everyone deserves a chance to read and write," "if you have deaf neighbors, you can help by learning sign language," and "persecution of religious minorities is wrong."

Despite the outcomes being a mixed bag, writing about such a long string of controversial issues demonstrates that the writers were interested in building a stronger sense of compassion among American viewers. If Star Trek used the future as a safe space to tell 1960s viewers "there's a better world coming," Bonanza used its period-piece status as a safe space to say "we already are, and have always been, capable of being better."

There is one notable hole in the overall better-world-for-all ethos, though: women's liberation. Bonanza didn't talk about votes for women, property rights for women, equal employment, or equal pay. A handful of episodes touched on the issue of domestic violence, at least one of which ended with the battered wife going back to her husband because "there are many different kinds of love."

Judge Judy's eye roll is courtesy of GIPHY

The fact that Bonanza ignored and/or bungled its coverage of women's issues stands out, considering a) how many other issues got attention and b) just how long Bonanza was around.

How long was it around?

A whopping 14 seasons (1959-1973), and 431 episodes. Later, it spawned 3 sequel movies (1988-1995) plus a prequel series (2002) - all of them produced by the indefatigable Dortort, a man who must've been immune to changing times.

This franchise steamrolled straight past the point where Pernell Roberts left the show, past the point where Michael Landon got too grey-haired to be called "Little" with a straight face . . .

. . . past the point where Dan Blocker died . . .

.jpg)

. . . and past the point where sanity should have prevailed.

To put this in perspective: Bonanza outlasted the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations, finally being canceled during Nixon's reelection campaign. It premiered two months after the first US casualties in South Vietnam, and ended 2 weeks before the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. People started watching Bonanza before humans had orbited the earth, and they were still watching Bonanza when Apollo 17 made the last trip to the moon. Babies conceived in the year Bonanza started were hitting puberty the year Bonanza ended. Bonanza was not the only TV show to film episodes at Spahn Ranch before the Manson Family moved in, but it was the only one of the bunch to still be airing new episodes when Charles Manson's death sentence got commuted.

And in that length of time, no love interest ever had a recurring role.

This sticks out more when you realize that Bonanza was a show with many, many recurring characters. It was somewhat famous as a source of steady gigs for bit players, who were a significant part of the show's world-building. Yet if you check Wikipedia's list of the top 12 recurring roles, some of whom appeared in over 100 episodes, you'll note that not a single woman makes the cut.

To be fair, this is partially explained by the historical context. In the 1860 census, men outnumbered women in Virginia City, NV by a ratio of 15 to 1: there were 2,189 male residents to 139 female residents.

Let's not give Bonanza a complete pass, however, because they had tons of one-off guest appearances. People passed through on stagecoaches, with traveling circuses, to mine for silver, on the vaudeville circuit, as part of wagon trains, or accompanying cattle drives. The Cartwrights also traveled around for their business, going as far away as Juarez, New Orleans, San Francisco, or even Australia as the plot demanded. So the fact that none of the four of them ever found a girlfriend who was worthy of a multi-episode arc was a writing choice, not a historical necessity.

Were there any women on this show at all?

Sure! Anytime a woman was needed for plot purposes, one would materialize with one of the aforementioned stagecoaches, circuses, vaudeville troupes, etc. She'd do whatever they needed a woman for, and then either leave again or be buried, according to how the writers were feeling that week.

What kinds of things did they need women for?

Well...

Uh...

Nothing good, usually.

The writers sometimes wanted to do a revenge plot, so they would have a woman be raped and/or murdered, inspiring her male relatives to start a feud. Other times, they needed a reason for a man with a troubled past to start over, so he'd get a daughter he needed to protect. Occasionally they gave one of their male criminals a conniving girlfriend, so that he could have a sympathetic reason for his crimes. Maybe they just needed to show off how much better the world would be if Cartwrights were making decisions for other people: More than once, the writers had Joe demand that a woman's brother, "let your sister make her own decisions," when he actually means, "let your sister agree with me, her boyfriend." In one especially memorable episode, they needed to have an unstable person burn down the whole city, because they were changing studios out-of-universe and wanted a reason for all the sets to look different. Who's a better plot device than a young woman who became a pyromaniac after her abusive father died in a fire, and has been burning buildings to cope with the stress of her engagement, but gets herself trapped in one of the fires and dies?

Well, I mean, the real-life Great Fire of Virginia City just started by accident, but that wouldn't be nearly melodramatic enough to pass muster as a Bonanza plot.

Even when a Bonanza woman showed clear character development, it could still come across as paternalistic. For example: in "Day of the Dragon," Joe wins a woman in a poker game after misunderstanding what his opponent (a slave trader) meant when he said he'd wager some livestock for the pot. The slave, Su Ling, then refuses to let Joe free her. It turns out that she's been badly abused in the past, and feels happier and safer when she belongs to someone who will take care of her. The Cartwrights beat her abusive ex-owner in a gunfight and get her set up with a chance to train as a nurse. She learns that "cages don't keep the world out, they just keep me in." Which is definitely the kind of moral an abused woman needs to learn!

Given the above, it should come as no surprise that "old maids" were used as punchlines on this show. Take, for instance, Meena Calhoun (Ann Prentiss), who appeared in 3 episodes across seasons 11 and 13. She's so desperate for a husband that she once tried to kidnap both Little Joe and Candy. In her final appearance, a man is forced to flirt with her because he owes her father $4.50 in gambling debt. Her reaction is to say, "In a way you've been quite flattering. The last fella Papa told to ask me out only owed him $1.06." Ba-dum-tss.

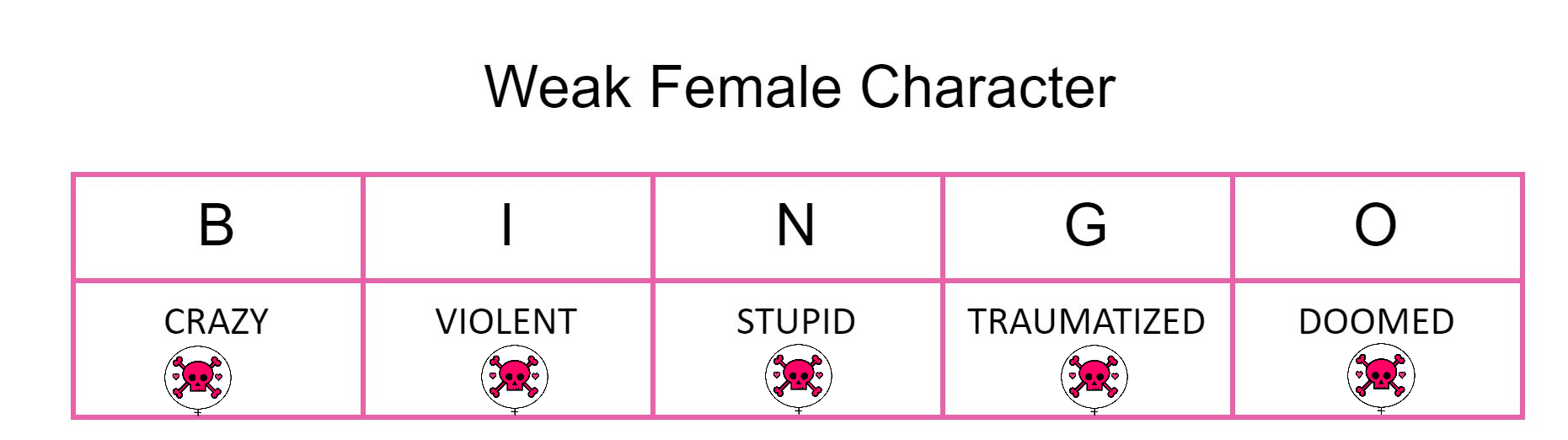

In short, if you think some modern shows struggle to give female characters such niceties as "inner lives" or "personal agency," Bonanza is an excellent way to remind yourself that TV has come a long way.

Were there any women behind the scenes?

Yes, to an extent. The producers were all men, and no woman ever directed an episode. But according to IMDB, there were at least half a dozen women who wrote episodes for the show. Interestingly, the list includes D.C. Fontana, whom we also encountered in our Star Trek analysis, and who contributed 2 episodes in the 9th and 10th seasons. The most prolific female writer for Bonanza was Suzanne Clauser, who turned out 8 episodes between seasons 6 and 12.

All of the credited female writers put together contributed to roughly 15-20 episodes, or less than five percent of the total. That is likely due to a combination of gender disparities in screenwriting at the time, and the show's creative structure. Dortort, as executive producer and head writer, is credited as the sole writer of most episodes. Besides him, the most prolific contributors were John Hawkins, with 29 episodes, and star Michael Landon, with 20 episodes.

Is there anything else we should know about Bonanza?

Seriously, I cannot stress enough that Bonanza was the defining show of American television for a long, long time. As I mentioned at the beginning, it stayed in the Nielsen Top 5 for 9 straight seasons. That means that up to 42 million people (aka 5 times the current population of New York City) watched it in a given week. It was so popular abroad that the stars toured Sweden and played to packed houses. In addition to the tie-in steakhouse chain, there were multiple musical albums and other successful merchandising endeavors. Today, careful viewers can see its influence on shows as disparate as Firefly and Supernatural.

Furthermore, a huge number of Bonanza's most passionate fans - including my own mother and mother-in-law - were little girls. So when Bonanza trotted out female stereotypes week after week, that had the potential to do real damage to small children's views of themselves. With all of the episodes about Real Issues, it's obvious that the show wanted to affect viewers' minds - to convince people to support good causes and see past stereotype. This show wanted to be part of a better world. But the consistent lack of good characterization for women demonstrates that it wasn't as concerned with trying to build a better world for the 50% of humans who are female.

Representation matters. Keep that in mind when we discuss the Cartwrights' dead girlfriends, next time on the #DFGRR.

.jpg)